The tax, included in the new state budget and replacing an annual pied-a-terre levy, would be a one-time payment that’s less likely to scare buyers away, brokers say. It’s just the entry fee into New York’s exclusive market.

“We probably dodged a bullet here,” Steven James, chief executive officer of Douglas Elliman’s New York City division, said in an interview. “It’s not the catastrophe we thought was going to happen.”

New York’s powerful real estate industry succeeded in killing the pied-a-terre tax that some considered “class warfare” against the rich, and a measure likely to hurt already-slowing luxury sales. While the higher mansion tax would apply to most buyers of homes costing $2 million or more, it won’t be a deal-killer for many people, brokers say.

Counting Pennies

Elizabeth Stribling-Kivlan, president of Stribling & Associates, said a client from Europe had canceled a house-hunting trip for an apartment above $25 million because of the pied-a-terre tax, which would have been levied each year based on the value of the home. The agent is hopeful he might now change his mind.

“It’s a lot easier to pay one time than every year,” Stribling-Kivlan said. “It’s easy to look at someone who makes an enormous purchase and say they have a lot of money. It does matter to them. But a lot of people get wealthy by counting their pennies and spending wisely.”

Read More: NYC Congestion Fee, Mansion Tax Ushered in by State’s New Budget

The pied-a-terre proposal, which had support from Governor Andrew Cuomo, collapsed after real estate professionals complained that it would damage sales and city tax officials said they didn’t have the resources to assess properties or determine who was an absentee owner.

Lobbyists also questioned the constitutionality of treating second-home buyers differently than permanent residents and whether legal challenges could arise when adjacent properties were assessed at different values.

Simpler Tax

The mansion tax has the benefit of being simple.

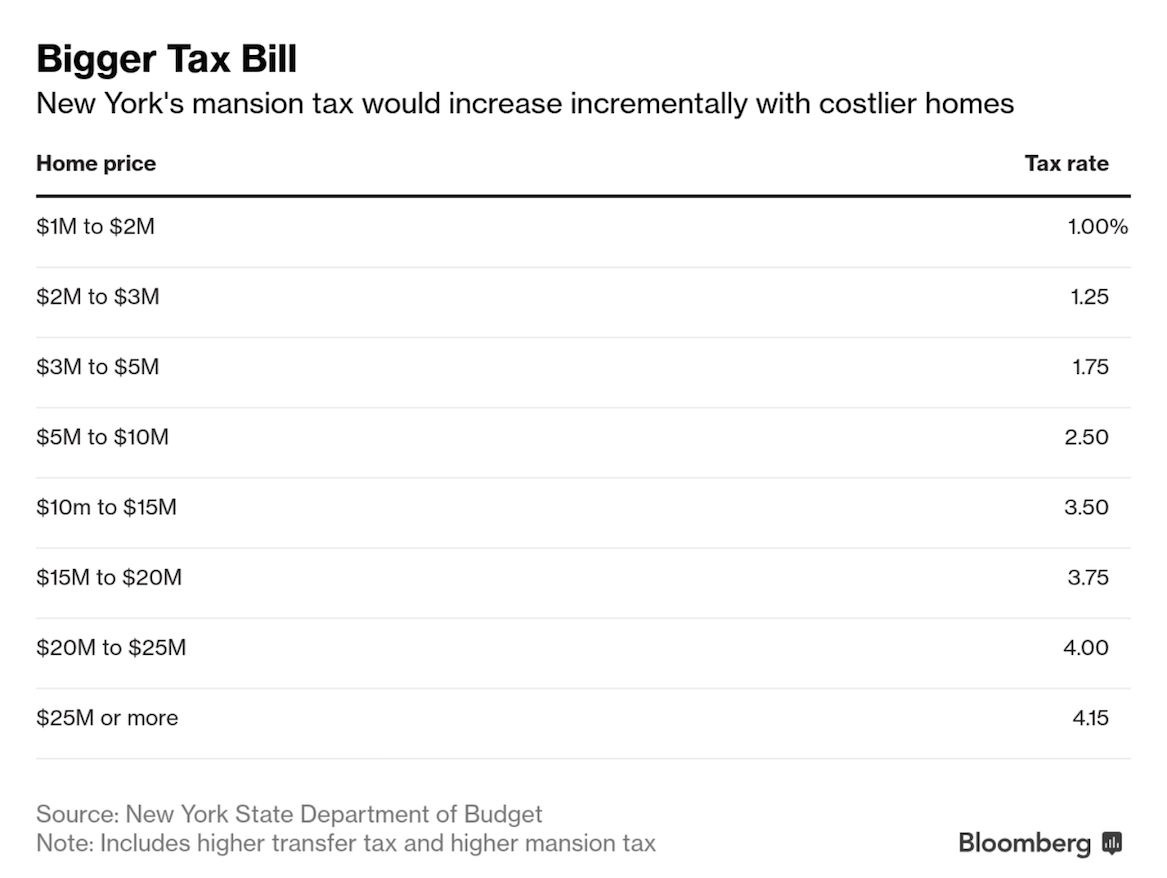

New York buyers already pay a flat 1 percent tax on home purchases of $1 million or more. Now, there would be a scale of graduated levies that would start at 1 percent. The rate would increase at $2 million and continue to rise until it reaches a top of 4.15 percent on any amount over $25 million.

Bess Freedman, chief executive officer of Brown Harris Stevens in New York, said she’s not happy about the new tax — but she’s relieved.

“Do we love it? No,” she said. “But we can digest it.”

If the levy had been in place for 2018, it would have affected about 26 percent of Manhattan’s residential market, or anything above $2 million, according to Jonathan Miller, president of appraiser Miller Samuel Inc. In Brooklyn, just 8.1 percent of deals were in that price range, he said.

‘Don’t Live Here’

To Pamela Liebman, president of brokerage Corcoran Group, the mansion tax is damaging to the whole market and a loud-and-clear message from officials that it doesn’t matter if the barrier to entry becomes unreasonable for big-spenders. In the past weeks, the brokerage has lost deals in the $25 million range over concerns about taxation.

“It’s particularly onerous on the high end, and these are people who have choices — they could buy here, but they don’t have to,” she said. “I have no issue with a small increase, but a 4 percent tax on expensive apartments is basically saying: Don’t live here.”

James Parrott, the economist whose proposal was the basis for the pied-a-terre tax legislation, says the mansion tax is both good and bad. On one hand, it will help pay for transit. But he also worries that it will be difficult to use the revenue for bonds because levies on home sales are lumpy, rising and falling from year to year.

Also, there’s the matter of fairness. Foreign buyers, for example, don’t pay income taxes, but the transit system and the city’s services contribute to the value of their properties, he says. The industry argues the opposite, saying wealthy second-home buyers spend money in the city while they’re in town and that bolsters employment from doormen to shop clerks on Fifth Avenue. And they don’t add kids to the schools or burden the transit system.

Still, it’s hard for the industry to declare victory, according to Parrott.

“They had to accept an increase in the mansion tax,” Parrott said. “If you call that a victory for them, OK.”